|

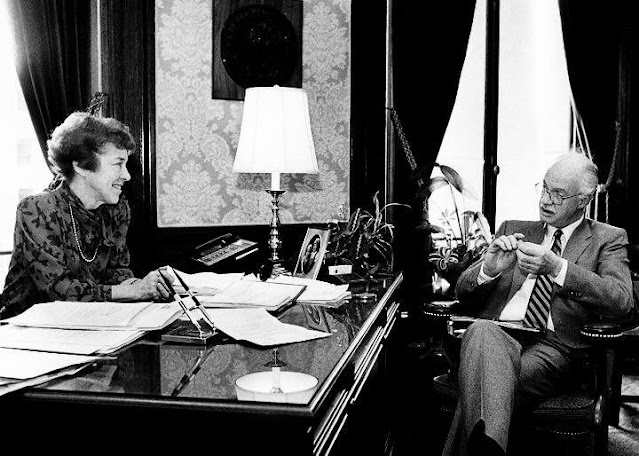

| The author's father, Alan Rowe with Sen Jeanette Hayner 1980s |

After my father died in 2017, two crates arrived on the doorstep of my house, sent by my beloved stepmother, Sarah, from the house in British Columbia she shared with my father.

The crates contained items that had been decided would someday be mine—a few favourite paintings from my parents’ art collection, some brass and silver artifacts from their travels in Cuba, Europe, and the Middle East; some leatherbound books, and family heirlooms, and photographs that had belonged to my grandparents and great- grandparents.

There were also more precious, personal things: a sterling silver napkin ring engraved with my grandfather’s monogram; an old shaving brush of my father’s with impossible soft, worn bristles; his Omega Seamaster watch from the year I was born; a battered velvet jewelry case containing his wedding ring in a small silver ring box engraved with a map of Bermuda, where my parents met and fell in love over the course of three days of whizzing around the island on my father’s mint-green Vespa scooter.

My father would have been the first person to say that he wasn’t a sentimental man, and that he prided himself on not looked backward, only forward. He was particularly unsentimental when it came to displaying personal trophies or even memorabilia.

Inside the boxes were some unframed, beautifully calligraphed documents relating to his diplomatic postings, going back to the early 1960s, carefully pressed between cardboard, likely by my mother, who was sentimental. But even she hadn’t framed these testimonials or hung them on the walls of his study in any of the houses in which I’d grown up.

In 1981, the summer of my graduation from boarding school, I was home with my parents in Ottawa, working two restaurant jobs and modeling in Montreal on the side. I was saving up money to travel to Paris that September.

Rummaging through a basement closet one rainy afternoon I found an ancient garment bag hidden behind a motley collection of winter gear in a basement cupboard.

Inside the garment bag was a cream-coloured linen suit I’d never seen before, slightly yellowed with age, but in otherwise perfect condition. The label was faded, but I could make out the words “Joseph Saarti” and “Beirut.” I tried the suit on. It fit my athletic eighteen-year-old body like it had been custom tailored for me, though it had clearly been custom-tailored for someone else.

I asked my father about the suit at dinner that night. At first, he didn’t know what I was talking about. When I described the suit, he said, “Good Lord, do we still have that? It must be twenty years old or more!” Turning to my mother he said, “I can’t believe you saved it, Penny.” My mother smiled and rolled her eyes in a way that communicated both gentle exasperation and love, because she saved everything, as he well knew.

My father told me I was welcome to “that old thing” if I wanted it. I thanked him profusely and hugged him in gratitude. With a young man’s not-atypical self-centeredness, it didn’t occur to me at that moment to note that my father had, in his thirties, been as tall and slim as I was at eighteen.

I wore the suit blithely in Paris that fall, and on several occasions afterward. The exquisite twenty-year old classic hand-tailoring blended flawlessly with the New Romantic style of the early-80s, and I was often complimented on my “retro suit.” I outgrew it around age twenty-four. The tailoring was just too unforgiving in its slimness, allowing only for the body of the thirtysomething Canadian diplomat for whom it was cut—or, grudgingly, his eighteen-year-old son.

Decades later, he asked me if I still had “that suit.” Absentmindedly I asked him which suit he was referring to, because I was by then well into middle-age, and I’d owned many suits. His eyes were very clear when he replied, “The suit I had made in Beirut. The one I wore to meet King Hussein. The one you found in the basement of the house in Ottawa that summer. Remember?”

Aghast, I asked why he hadn’t told me about the suit’s provenance, or its history. I’d thoughtlessly worn it to smoky parties in the basements of frat houses. I’d even spilled cheap red wine on it once, on a date that had gotten very handsy very early on in the evening. And when it hadn’t fit me, I’d given it away to a younger, thinner friend because I hadn’t wanted “my” suit to go to waste.

“It was special to you,” I told him, appalled with myself. “It had history. You should have told me about it, Dad. I would have…well, I would have treated it differently.”

My father shrugged. “Oh, Michael,” he said. “It was just a suit. You think too much about these things. You know I never do.”

Years later, going through one of the many stacks of papers he’d sent me since the death of my mother in 2020—personal esoterica, drafts of his unpublished memoir, letters, photographs of my grandfather’s childhood in Saskatchewan, cards I’d made for him and letters I’d written to him as a child, I did indeed find a small, fuzzy black and white photograph of my father wearing that cream linen suit.

In it, he is tall

and impossibly angular, the most junior of the assembled embassy delegation,

shaking hands with His Majesty King Hussein bin Talal of the Hashemite Kingdom

of Jordan, on the tarmac of the Beirut airport in a blaze of impossibly bright Middle

Eastern sunlight.

Sifting through memories of my father on Father’s Day, I select the ones I cherish the most, and I replay them in my mind like Kodachrome slides on a mechanical carousel.

There I am at five with my father, riding a cable car up a mountain in Lebanon. I can smell cold sky and fresh cedar through the window. His arm is around me; the soft wool of his sweater is warm against my skin, and there is a faint scent of Bay Rum aftershave in the fibres. Later, we are flying my Mary Poppins kite in a meadow, and both of us are blowing her kisses and laughing.

In yet another, I hear a sharp, angry shout from the bathroom of our house in Havana, followed by the sound of the wall being kicked hard several times. My father has found a scorpion nestled in his shoe and has crushed it with his toe before it had time to wield its tail to strike—my father as the fearless hero against whose strength no foe could prevail, not even a scorpion.

And of course, my favourite memory: my father, holds my hand on a riverbank in 1971 as I weep disconsolately over a pet turtle I lost when a neighbour’s dog tore the turtle’s pen apart in our backyard. He’d picked me up, carried me to the car, and driven me to the edge of the Rideau River, and pointed at the mud and brackish water. That’s where your friend went, Mike my father tells me. He’s all right. He made his way to the river to live here instead of in his pen in our backyard. He wanted to find turtle friends. When you think of him, think of him here, by the river. And because my father had said it was so, it must be so, and there was comfort in that great, generous, preposterous, loving lie.

There are other memories too, of course—terrible screaming fights with my father as I left childhood and entered adolescence; slammed doors, tears, fury, the feeling of being deliberately misunderstood and perpetually disapproved of. The latter feeling lasted well into adulthood.

As loving and tender as he was, my father was also able to weaponize his sonorous voice to devastating, withering effect. As I’ve learned in later life, having been the unintentionally hurtful one on more occasions than I’m proud to admit, I’m no longer sure that he knew how wounding he could be, or how shattering it felt to be put in my place by him.

It took decades for some of those wounds to heal, on both sides, because for every unreasonable expectation he had of me, I had at least one of him. Neither of us could quite seem to be the man the other needed him to be. Nor would either of us willingly yield, and together we could shred the peace of our family until it was hanging in eels.

In December 2007, my father and Sarah decided to join us in Palm Springs at the home of my best friend Ron and his husband, Eric.

Whatever Brady Bunch fantasy I’d entertained about cozy 70s sitcom Christmases replete with and smooth, healing reunions vanished in a puff of smoke the minute my father walked through the door.

At the end of the holiday, Ron, who knows me better than anyone on earth I’m not married to, took me aside and said, “You know, you and your father are very much alike. You sound like him, you react like he does, and you even walk like him. No wonder you’ve been at each other’s throats all this time. You’re practically the same person.”

And my father’s life with Sarah, following my late mother’s death in 2000, was ultimately good for both of us. Aside from literally loving my devastated father back to life, and pushing him back into life, she was a peacemaker. Over time, there was more than a just a thaw, there was a warming. We sat at the kitchen table in their house in Victoria after dinner in the evenings and talked about life, or family. We had both been journalists at various points in our lives and, as two grown men with significant mileage, politics was something we could now discuss passionately, but objectively, and without rancour. The tension lessened, and a new ease lent itself. We joked about having been a father and son tag-team of interviewers: he had interviewed Sophia Loren for the radio in Holland in the 1950s; I had interviewed her film director son, Eduardo Ponti, on a film set in Toronto.

One evening, my

father apologized for something that had occurred when I was twenty-one. It had

been something scarring, and I was stunned to hear him acknowledge it. But the

floodgates opened. I had apologies of my own to make, and I made them. We held each other for a bit, then had the deepest, most healing, most honest, most

forgiving conversation of our lives.

I gave my father’s eulogy at his memorial service on a brilliant Pacific Northwestern day in August 2017. I nearly made it all the way through without breaking down. Of course, I broke down. I am unabashedly, unashamedly sentimental. Afterwards, at the reception, an elegant, expensively dressed woman came up to me. She introduced herself, then leaned in as though to share a confidence.

“You know,” she purred. “Your father had a beautiful speaking voice. So resonant and strong. You could tell he’s had a career as a radio announcer before he entered the foreign service.” I averred that yes, he did indeed have a beautiful speaking voice. The woman made a little moue with her mouth, then added, “It’s really too bad you didn’t inherit it.”

I stared at her blankly for several seconds. Then I started to laugh. Not unkindly, though it was an incomprehensibly bizarre thing to say to a grieving son who’d just sobbed his way through the second half of his father’s eulogy.

I laughed because

I felt my father’s spirit move in me at that moment, and because I’m regularly

told how much I sound like him, and because, even if I didn’t sound like

him to her, I inherited everything else from him that counted. And

because my father would have laughed just then, too.

In East, West, Salman Rushdie wrote, “At sixteen, you still think you can escape from your father. You aren't listening to his voice speaking through your mouth, you don't see how your gestures already mirror his; you don't see him in the way you hold your body, in the way you sign your name. You don't hear his whisper in your blood.”

As memories mellow and deepen, and as they run to amber, it becomes easier and easier to see the totality of the people we've loved and lost, and to measure their triumphs and failures as human beings, knowing that we are also human beings with our own flaws, and to leaven those memories with that very love.

My father is in me, and he is everywhere. His portrait, by the Cornish artist John Cabell, hangs in the dining room. I have his Italian burled walnut valet stand in my bedroom. I had his Omega Seamaster restored, and I wear it daily on my wrist.

I occasionally even shave with his shaving brush, though not often. The bristles are almost too soft and I’m not really a “brush man” anyway. I’ve shaved in the shower since I was a teenager, when mirror space in the steamy communal bathroom at school was always at a premium.

Good Lord, Michael, I can imagine my father intoning. How

can you see to shave in the shower without cutting your face all to hell? Use.

The. Mirror.

When I was twenty-five, that would have driven me mad. Today it just makes me smile to imagine it. I shake my head and wish I could hear it from his own mouth, in that marvelous golden voice he had, instead of just in my imagination.

There have been many times since my father’s death when every fibre of my being has ached for his wise counsel.

In most cases, I already know what he'd say after addressing the specific issue, and dispensing advice that has, more times than not, in my life, turned out to be wise counsel. It would always come back to moral strength, integrity, decency, being true to yourself, and doing the right thing, even when that's the most uncomfortable, even painful, option. There was, and is, infinite comfort in that.

I wish I could reach out and hold him again, just once—gently now, remembering the way those strong, wiry shoulders went as brittle and fragile as winter branches in his old age—and press my love into his body so that he feels it, like heat, in a way he couldn’t always hear it.

I was formed young in the crucible of my father’s love and protection. As men, we often grow into adulthood with a very clear sense of ourselves in relation to our fathers, or our father-figures, if we’re lucky enough to have them—the ways in which we are determined to be like them, or, in other cases, to be as different from them as possible. I suspect that, in most cases, it’s some sane combination of both.

The best of my father is with me always, and the rest fades away. As Rushdie wrote, I still hear his whisper in my blood.

|

| Alan Rowe by John Cabell 2010 |

|

| Alan Rowe early 1930s |

|

| Rowe family mid-60s author with his mother |

|

| Penny and Alan Rowe 1967 |

|

| The author's parents aboard the QE2 1977 |

|

| The author with his father and stepmother Sarah 2005 |

All photos supplied by the author. Used with permission.© 2023 Michael Rowe. All rights reserved.

|

| The Author |

Just beautiful. Thank you for sharing this with us.

ReplyDeleteA wonderful, well-written memoir that touches on the universal father/son dynamic. A shame that so much goes unsaid while our fathers are alive, and our understanding and insights only appear after they've departed. This is a Father's Day treat. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteYou have wonderful memories. You are fortunate. Not everyone makes that claim. Yes, I think you are right. There is a combination of the desire to be different and the good qualities we inherit that make us our fathers’ sons. I like to think it was my father’s sense of fairness and equality that helped make me the man I am. My parents were from the countryside. My mother, in particular, was drawn to the Sound. We made the obligatory seaside Sunday drives in search of her favorite ice cream, maple walnut. We always found it. Everyone satisfied with our cones, it was time for a lesson in society’s unfairness. He often drove us home through neighborhoods where the poor lived. His voices resounds today, “we are no different from the people you see here. It is not their fault they don’t live in neighborhoods like ours…” He didn’t have to make that detour on the way home. But he did. “Teach your children well.”

ReplyDeleteWhat a lovely and touching Father's Day essay. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing this. Men of your father’s (and mine) era shared many traits. I enjoyed reading this

ReplyDeleteThank you, so very much for sharing ypur family memories. Truly priceless.

ReplyDeleteDuring long drives my dad would listen to us silently doing whatever we were doing in the back seats of the various cars we had during our childhoods. On occasion he'd quietly speak up with the comment "Let me tell you about something I've been thinking of." It often happened after dark when we were tired of the long day on the road and n need of 'bedtime stories'. We listened because it was almost always a story about America and how Americans came to be. He was an educated man but not pedantic. He made the stories come alive with vivid imagery and deep background about the history of each of the times and how no one knew what the future would hold. We were held in rapt attention and it was something I adopted with my own children. They have told me those 'story times' have been some of the most enjoyable and meaningful memories of their childhoods. It was fun thing to do and I'd often throw in something clearly wrong just to keep their attention: "Oh Daddy, you're making things up again!!" and they'd laugh as I insisted "No, no, no. It's all true I tell you!" (when obviously not).

ReplyDeleteBrought me to tears. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteBeautifully written and very poignant. Thank you for sharing Michael's story.

ReplyDeleteHow lovely. It was just the right thing, at just the right time. Thank you.

ReplyDelete